Finding The Lady of Bandama: A Unique Species

You have to up early and very lucky to find the Bandama Caldera full of mist like in Lex's photo. It only happens a few days every year and clears as soon as the sun starts to warm up.

However, there is a lot of stuff to see and do in and around the caldera other than drive to the top of the cinder cone and look at it. You can walk around it, down to the crater floor, visit the aboriginal caves, and the secret bunker (when the visitor centre reopens).

The Lady Of Bandama

A few days ago we walked down to the caldera floor to find something truly unique.

Parolinia glabriuscula, know as the Dama de Bandama or Bandama Lady, only grows inside the walls of the caldera. In fact, it only grows on the cliffs at the southeastern end of the caldera and on the scree at its base.

To be honest, the Dama isn't the most exciting plant in the world to look at. It's similar to other Parolinias growing in other places around the island (Guayadeque, the southern slopes of the island, etc).

What makes it special is that it is critically endangered and only grows in a tiny area: Definitely unique enough to walk across the Caldera floor to find; especially in January to March when it produces its little white flowers.

It seems to be thriving now that goats no longer graze inside the Caldera (and now the aggressive donkey has gone). There are far more plants than I remember when I was a kid and they have spread down the scree slope and almost onto the floor. Good news that is being repeated all over the island now that most goats are kepet bpenned in rather than roaming free.

ALEX SAYS: I was with my mother, a botanist, when she discovered the Dama de Bandama back in the 1980s. We were walking around the crater rim and spotted the only one growing outside the caldera.

Everything you need to know to walk down to the caldera floor is in our Gran Canaria map. We haven't marked the caves because we want to go back and make sure they are still safe to reach.

Note that the Hoyos de Bandama winery tends to have fairly erratic opening houtrs so if you see it open, head in for a glass of wine. The Caldera dry white is one of Gran Canaria's best.

Tried and Tasted Guide to Canary Islands wine

Welcome to the Tried and Tasted Guide to Canary Islands wine

It’s a guide for the enthusiastic wine drinker who wants to know more about the unique grapes and wines of the Canary Islands.

Once you’ve read it, you’ll know enough about Canarian wine to recognise a good Malvasía and know why La Palma wines taste of pineapple and Tenerife wines of almond blossom.

TRIED AND TASTED: CANARY ISLANDS WINE

Millions of people a year drink Spanish wine in the Canary Islands without realising that they have a thriving wine industry.

It’s a huge shame because as soon as you start to explore Canarian wine, you find that it’s more than a tourist gimmick. With hundreds of wineries and dozens of local grape varieties, the Canarian wine scene has something for everyone and is a vital part of the rural economy.

What’s special about Canarian wine

John Keats: Lines on the Mermaid Tavern

Have ye tippled drink more fine

Than mine host's Canary wine?

Three things make Canarian vines and wines special...

Ancient grapes

The Canarian flora is a living fossil with over 600 species of plants that grow nowhere else on Earth. These remnants of an ancient Mediterranean vegetation that was squeezed into oblivion between the ice of Europe and the Sahara desert.

Canarian plants survived on the Atlantic Islands thanks to the temperate Atlantic Ocean.

Millions of years later, the grapevines of the Canary Islands pulled off a similar feat of survival.

In the 1860s, an American vine aphid known as phylloxera hitched a lift across the Atlantic on one of the first steamships and ravaged continental Europe’s vineyards. The bugs fed off the roots of European vines and spread a deadly fungus.

Growers tried everything from putting toads next to their vines to massive doses of chemicals, but nothing stopped their vines from withering.

Many ancient varieties died out completely and the survivors had to be grafted on phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks. Within a few short years, Europe’s vineyards,and the taste of the wines they produced, had changed beyond recognition.

The taste of ungrafted pre-phylloxera wine has gone forever, except for a tiny number of wildly-expensive bottles coming from few patches of pre-phylloxera vines that survived in volcanic soils across Europe. Even in these areas, the original vines were replaced with modern varieties.

However, in the Canary Islands, phylloxera never struck and the vines that grow today descend directly from the original plants brought from Europe.

Canarian vines are therefore the only vines on Earth that can trace their lineage back to the vines brought to Hispania by the Ancient Greeks and Romans.

Recent genetic studies have shown that several Canarian grape varieties, such as Tintilla, Marmajuelo and forastera blanca, have no known ancestors. It’s likely that their ancestors died out during the phylloxera plague of the 1870s leaving them as the last of their kind.

Like the laurel forests, viper’s bugloss flowers and houseleeks, Canary Islands grape vines are living fossils.

But they taste much better.

500 years of adaptation

Vines came to the Canary Islands from Spain, and from Madeira island to the north, as early as the 1450s. Since then, they have slowly been adapting to local conditions. Growers use cuttings from the vines that are best adapted to the local weather and soil to populate new vineyards.

The result, after 570 years, is vines that thrive in the local climate and soils and produce wines as spectacular as the islands they are from.

The Canarian climate and terroir

The Canary Islands climate is one of the best in the world, at least for people.

From grapevines, it’s more of a challenge; the African sun and young volcanic soils packed with minerals mean that grape vines are at the edge of their comfort zone.

The results is grapes packed with sugar, minerals and character and wines with intense aromas and flavour; Great for the whites, but more of a challenge for the reds.

A brief history of Canarian wine

William Shakespeare: King Henry IV

You have drunk too much Canaries, and that´s a marvellous searching wine

Canarian wine was once a global superstar exported to three continents.

However, the Canary Sack of Shakespeare fame was fit for drowning a Duke but not for modern supermarket shelves. It was a strong, sweet drink and a long way from the dry, fruity wines popular today.

Origins

The Canarian wine industry started in the 1450s as soon as the Spanish took control of the islands from the original inhabitants. However, the first European vines were imported as early as the 1350s when the first missionaries arrived on the islands.

However, the recent discovery of grape seeds in a pre-Hispanic settlement in Tenerife is a tantalizing hint that the island’s aborigines brought vines with them centuries earlier.

Boom & bust

Wine wasn’t a big export until the sugar cane export industry collapsed.

Faced with cheap sugar from Caribbean and South American plantations, Canarian farmers turned their hand to making wine.

By the mid-16th Century the islands, and especially Tenerife, were exporting sweet Malvasía wine to the New World, Britain and Europe. By the 17th Century the islands exported most of their wine to Britain.

The rot started in 1666 when a British company tried to monopolise the trade and got chucked out of Tenerife. Britain responded by banning imports of Canary wine.

The next year, Charles II’s Portuguese wife persuaded him to favour Portuguese wine and the 1701 War of the Spanish Succession forced British wine merchants out of Tenerife for good.

The Canarian wine trade with Britain faded as it turned to Portugal and Madeira for its booze; wine-making in the Canaries spent the next 150 years as a domestic industry.

By the start of the 19th Century, Canarian and especially Tenerife wine was back in-demand in Britain and the Americas. By 1863 the islands were producing 40,000 pipes (about 500 litres per pipe). However, attacks of powdery mildew disease in 1852 and 1878 set everything back again.

Another recovery followed, but was stymied by the First World War. Canarian wine faded completely from the scene.

Until now.

Canarian vines in the Americas

The first vines planted in the Americas, known as Mission grapes, are descended from the Listán Negro or listán prieto variety growing in the Canary Islands in the early 16th Century.

Spanish colonists took vines from the Canaries rather than transport them all the way from Spain. Missionaries then spread them throughout the Americas, up into the United States and down into South America (where it is known as criolla).

Worth paying: The price of Canarian wines

William Shakespeare: Twelfth Night

O knight thou lackest a cup of canary; when did I see thee so put down

A common complaint amongst casual wine drinkers in the Canary Islands is that Canarian wines are more expensive than imported Spanish wines.

This is unfair as you simply can’t compare the two.

The rugged geography of the Canary Islands means that local vineyards are tiny and all the vine maintenance and grape picking has to be done by hand. Consequently, there is no way the Canarian wine industry can compete on price with vast, mechanised Spanish vineyards.

And it shouldn’t have to.

Instead of comparing Canarian wine to cheap, branded Riojas from vast estates, compare it to single-estate wines made from hand-picked grapes.

Good luck buying one from anywhere for less than 15 euro a bottle.

Quality Canarian wines, on the other hand, start at 6-8 euros per bottle in the shops.

Given the work involved in harvesting and making the wine, their pre-phylloxera history, and the vast range of unique local grape varieties and microclimates, Canarian wines are superb value.

Supporting local and rural life

Another huge benefit of drinking Canarian wines is that you support local farmers and wineries that keep the Canarian countryside looking spectacular.

Without wine, large areas of Lanzarote would be abandoned and centuries of tradition lost. The same goes for rural La Palma, the Gran Canaria highlands and huge areas of Tenerife countryside.

Think of drinking Canarian wine as a pleasant way of supporting local life and of offsetting those carbon emissions from the flight to the islands.

Then open another bottle.

Canarian wine varieties

Robert Louis Stevenson: The Black Arrow

A little good canary will comfort me the heart of it

Identifying Canarian grape varieties is a headache. Each has several names depending on the island, area and even estate where it grows. Recent genetic studies are unravelling the mess but often add as many mysteries as they solve.

For example, a recent study found that there are over 20 different varieties of Malvasía vine growing in the Canary Islands. One grows in a single vineyard in Lanzarote.

The situation is further complicated by wineries focusing on the unique nature of their grapes in order to appeal to patriotic local buyers,and by the fact that Canarian microclimates mean that identical vines produce very different wine even in adjacent wine areas.

Is Lanzarote’s diego grape the same as Gran Canarian Vijariego blanco, or El Hierro verijadiego, or Tenerife’s bujariego? Is Listán Negro different from Listán Prieto?

Nobody knows, but everybody has a strong opinion, especially after a few glasses of vino. The truth is that it hardly matters. The quality of the wine is more important than the grape it came from.

And the terroir of the Canary Islands is so varied that the same grape does very different things depending on where it’s grown.

Canarian white grape varieties

The different Canarian DOs allow over 20 white wine grape varieties but these are the most common and interesting local ones.

Malvasía

The star of Lanzarote, but also planted widely in southern La Palma and Tenerife and grown on all the islands. Malvasía is originally Greek and comes in white, pink and red forms, although almost all Canarian Malvasía is white.

You sometimes see Lanzarote Malvasía referred to as ‘Malvasía Volcánica’. The theory is that it has changed so much to adapt to local growing conditions that it is now a separate variety.

Not to be outdone, Tenerife and La Palma growers call their Malvasía ‘Aromática’.

Tasting Notes

Malvasía wines have a floral or fruity bouquet with hints of white fruit, orange blossom and honeysuckle.

In the mouth they present strong notes of peaches and apricots (some say white currants, but we’ve never even seen one) along with citrus and blossom. They feel quite full or fat in the mouth.

Good Malvasía wines have a zing to them; like there’s a tiny bit of sherbert in each sip that lifts all the flavours.

Albillo / Gual

Local wine buffs argue for hours about whether Gual is the Canarian name for the Spanish Albillo grape or whether it is a variety in its own right. Both names are used on bottles and the flavours are similar.

Albillo/Gual is common in Tenerife but also grown on El Hierro and northern La Palma, where it is called Albillo Criollo and produces fabulous whites. The Gual name is used in Tenerife.

Wines made from Albillo and Gual last well in the bottle.

Tasting Notes

Albillo produces golden coloured, slightly sweet wines with tropical fruit, jasmine and honey notes but little aroma. A high level of glycerol makes them rich and smooth in the mouth.

Gual is said to be slightly more aromatic and to bring oak notes to wines that aren’t stored in barrels.

Try the Viñatigo Gual varietal from an excellent example of a Gual wine, and any La Palma Albillo for those tropical notes.

Listán Blanco

Closely related to the palomino sherry grape and popular in the Canary Islands because of its high yield and drought resistance, Listán Blanco is the most common white grape on all the islands except Lanzarote and La Gomera.

While Listán Blanco isn’t valued in Spain, it produces some great wines in the Canaries.

Tasting notes

Listán wines are pale and greenish-yellow in colour and don’t have much mouthfeel.

At their best, Listán Blanco wines are crisp with balanced acidity and fruity flavours (melon, green apple, citrus peel) and fennel notes. They have a bitter or astringent, but not unpleasant, aftertaste.

Canarian Listán Blanco wines also have a pronounced minerality in their aroma and taste.

Bad Listán Blanco wines lack acidity and body, and can taste of burned rubber.

Sparkling wines made from Listán Blanco are light and quaffable but tend to lack any serious character.

Vijariego Blanco

A Canarian grape variety most common on Tenerife and El Hierro. Vijariego blanco grapes are used in Tenerife to make sparkling wines as they are high in sugar and acid.

Also known as bujariego, diego and verijadiego.

Tasting notes

Vijariego wines are fresh with green apple, pear, grassy and citrus peel notes, although they are low on aroma.

Vijariego is often combined with aromatic but less acidic varieties such as Listán Blanco (as in Viña Frontera from El Hierro).

Marmajuelo

A Canarian grape with no known ancestors that is best described as a temperamental little blighter.

Marmajuelo often refuses to set fruit for no apparent reason so it is only grown in significant quantities on Tenerife and Gran Canaria; A real shame because when in the mood, Marmajuelo produces superb wines.

Also known as Vermejuelo and Bermejuela.

Tasting notes

Marmajuelo wine is golden and aromatic with strong mineral, pineapple, custard apple and passionfruit notes.

It also smells and even tastes of fig leaves (crush and sniff one while you are in the Canaries and you’ll know what we mean).

Moscatel

The most aromatic and grapey of grapes, moscatel is traditionally used to make intense, sweet wines but is also used to beef up wines made with other varieties like Listán Blanco that can lack flavour.

This can be a good thing as moscatel adds fruitiness, but it can also be abused. If you get a wine that tastes slightly of raisins, then there’s a good chance that the winery has gone over the top with the moscatel juice.

Tasting notes

Used right, moscatel adds a floral aroma and grapey taste to white wines. It can also make them dull and raisiny.

In sweet wines made by traditional methods, moscatel is elevated to a different level and produces wines that taste like nectar.

Forastera Blanca

La Gomera’s star grape, Forastera Blanca accounts for over 90% of its vines although small amounts also grow in Tenerife. It is another Canarian variety with no known ancestor and has grown on the island since at least the 1450s.

Tasting notes

Wines made from Forastera Blanca grapes are straw-yellow in colour, of decent acidity with hints of green fruit and plenty of minerals. Tropical fruit and white flower notes can also come through.

White wine styles

Canary Islands white can be divided into four main styles.

- Dry & fruity: Wines made from Malvasía, Forastero Blanco and coupages of Listán Blanco and other grapes.

- Delicate & fruity: Listán Blanco wines

- Rich & fruity: Wines made from Albillo, Gual & Marmajuelo grapes

- Dry & acidic: Wines from Vijariego Blanco grapes.

Canarian red grape varieties

Over a dozen red wine grape varieties are allowed in Canarian reds but most are rare. There’s also a growing and controversial trend towards planting non-native varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot.

Here are the most common and interesting local varieties.

Listán Negro

Because of its high yield, Listán Negro is by far the most common red grape variety grown in the Canary Islands. It is the star of north Tenerife’s wineries but is grown all over the Canary Islands.

It is not related to Listán Blanco.

Listán Negro produces lively young wines full of red fruit and spice, especially when fermented by carbonic maceration.

To make traditional Canarian red wine, listán is often blended with more acidic varieties such as Negramoll to produce light-to-medium-bodied reds with black fruit flavours and a hint of spice.

It’s also known in the Canaries as Listán Prieto, although some (of course) regard this as a different grape.

Listán Negro is what give many Canarian wines their characteristic flavour.

Tasting notes

Canarian Listán Negro wines are light on the tannins and heavy on the minerals with red berry, black fruit and even banana flavours. They have an aftertaste that is reminiscent of the faint smell of gunpowder.

Rosé wines made from Listán Negro have intense berry flavours but tend to be one-dimensional and lack acidity (any Canarian rosé that tastes or black mulberries or blackcurrants is made from Listán Negro).

Negramoll

The high-yielding workhorse grape of Madeira island to the north, Negramoll is also grown in southern Spain and called mollar cano. It grows all over the Canary Islands but yields rather bland varietal wines and is almost always used in blends where it adds acidity to tastier grapes like Listán Negro.

Also known as Mulata

Tasting notes

Negramoll wines are earthy and quite acidic with hints of strawberry and cherry. They can have an unpleasant metallic aftertaste.

Tintilla

An odd local variety that is low-yielding but disease resistant and produces robust wines with ageing potential. Tintilla wines contain tannins without needing to go into oak barrels.

This variety has no known ancestor or relative anywhere in the world and is probably descended from a Spanish grape that was wiped out by phylloxera.

Tintilla is used to add intensity and colour to other grapes as was rarely cultivated on the scale needed to produce varietals.

Tintilla is grown all over Tenerife and also on La Palma, La Gomera and Gran Canaria.

Tasting notes

Tintilla wines are aromatic and fruity with lots of spice and tannin and a definite hint of tobacco.

Babosa Negra

A rare local variety than can produce both sublime and dreadful wine. It’s low-yielding and varietals are expensive.

Also known as Bastardo Negro, and presumably named by a grower who couldn’t get it to do what he wanted.

Tasting notes

Picked at the right time and well-treated, Babosa Negra produces silky, slightly sweet reds that stand proud. However, pick it too soon or ferment it carelessly and Babosa Negra yields sweaty sock juice.

Castellana

Often confused with Tintilla, Castellana or castellana negra is a Tenerife grape that has recently been recovered and is getting growers hot under the collar. However, it’s still only a minor variety and is most often blended with fruitier grapes like Listán Negro.

Tasting notes

Castellana produces intense wines with plenty of acidity along with earthy, black fruit, mineral and liquorice notes.

Vijariego Negro

Cultivated in Tenerife and El Hierro, Vijariego Negro is normally added to other grapes but you can buy varietals.

Tasting notes

Vijariego Negro produces wines that are a pale brick red in colour but intensely fruity with hints of pepper spice.

Red wine styles

Typical Canarian red wine is high mineral, fruity and spicy due to the blend of Listán Negro and Negramoll or Tintilla grapes; Listán provides the fruit and spice, Negramoll and Tintilla the acidity, and all contribute minerals.

The listán / Negramoll combination is typical of the Tacoronte Acentejo DO in Tenerife, but most Canarian reds contain one or both of these grapes. The result is wines that reflect the volcanic soils and strong sunshine of the Canary Islands; Lively mouthfuls of minerals, fruit and spice with that hint of gunpowder in the aftertaste.

Sweet Canary wine

The original white Malvasía wines so popular amongst Shakespeare’s crowd were far sweeter than modern fashion allows. Most wineries nowadays focus on making highly quaffable dry and slightly sweet whites full of freshness and fruit.

However, the tradition of making sweet wines in the Canary Islands hasn’t disappeared completely. In the countryside, bars still have a barrel of sweet wine for the locals, and plenty of wineries still make a few bottles of the stuff.

Canarian sweet white is made from Malvasía and moscatel grapes, and the red from Listán Negro and Pedro Jímenez.

Sweet wine in the Canaries, often called vino de licor, is made in two ways. Most, and all of the cheaper stuff, is partially fermented grape must mixed with grain alcohol to produce a sweet, wine-flavoured liqueur.

However, some wineries, mostly in Lanzarote, La Palma and Tenerife, still make sweet wines by letting the grapes ripen and start to shrivel on the vine, then fermenting them and letting the resulting sweet and highly alcoholic juice rest in barrels for several years. The barrels lose liquid and the flavours are concentrated into an intense, sweet wine known as soleraje.

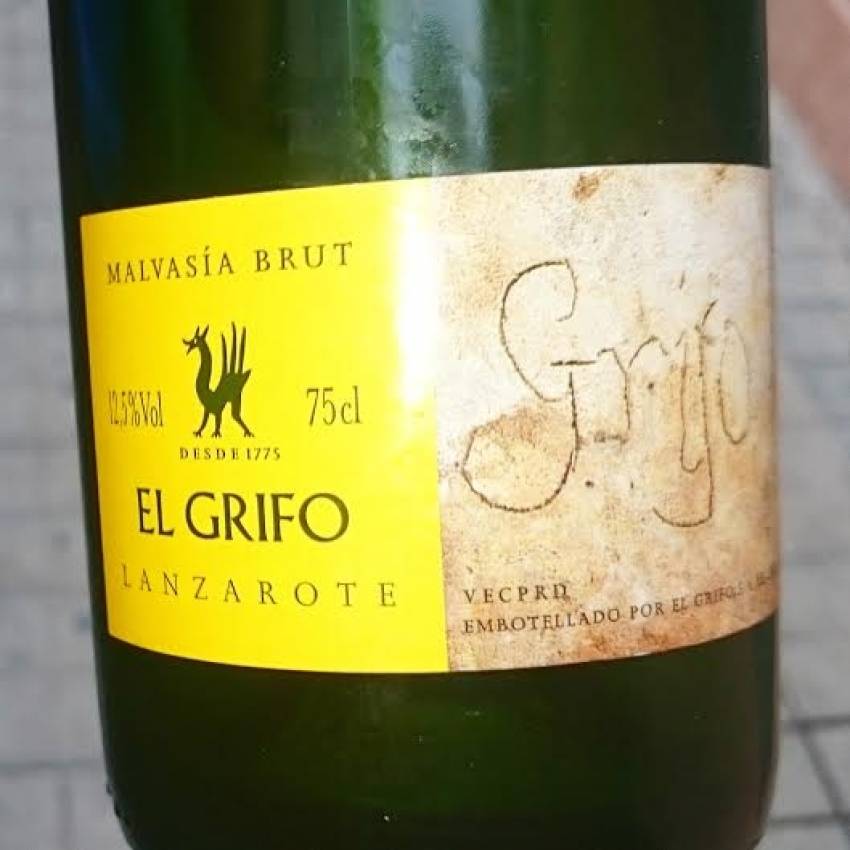

This technique is used in Lanzarote to extract maximum flavour from sweet wine made from Malvasía grapes. The El Grifo bodega, the oldest in the Canary Islands, makes a sweet white called El Grifo Canary that contains wine that was laid down in the 1950s.

We’d recommend trying Canarian sweet wine in a good bar or bodega as decent bottles cost upwards of 50 euros.

It’s a mystery why no Canarian winery has experimented with the fortified wines so popular in Madeira island just to the north of the Canary Islands.

Pine wine

In the days before oak barrels were easy to get hold of, La Palma winemakers kept their wine in barrels made from tea: Canary pine heartwood. The result was a resinous wine similar to Greek retsina.

While vino de tea is now rare some wineries in La Palma still make it, although they limit the time the wine spends in contact with pine. The result is wine with a hint rather than a whack of resin.

Island by island

Walter Scott: Bride of Lammermoor

But the no harm in drinking to their healths, and I will fill Mrs. Mysie a cup of Mr. Girder´s canary

Spanish wine areas are classified into zones called Denominaciones de Origen (DO). Each has a governing body that controls the quality and character of the wines it produces.

Every Canary island has its own DO except Tenerife, which has five, and Fuerteventura, which is just too hot and dry for grapevines (although a couple of brave souls are trying in the south).

There is also an Islas Canarias DO for bodegas that ship in grapes or must from different islands to create blends.

Some are snobby about bodegas that make DO Islas Canarias wines, but the flexibility they have to blend juice means that they make some of the best Canarian wines.

If a wine doesn’t have a DO sticker on the back of the bottle, then it’s probably imported from Spain in tanks and bottled in the Canaries. The wine may be lovely, but it’s not local.

The exception to this is wines that are bottled for local consumption (family, friends and village only) and don’t have a label at all. These vary from ‘oh my god, that’s abominable’ to ‘this is quite nice, actually’.

In general, if a local wine is good enough to sell it gets a label.

The maturing Gran Canaria wine industry

Gran Canaria is probably the island with the greatest untapped wine potential.

While Lanzarote has its zingy Malvasía, La Palma its rich Albillos, Tenerife its boisterous Listán Negro reds and delicate Listán Blanco whites, Gran Canaria is still searching for its signature wine style.

Perhaps the most variable island in the Canary Islands doesn’t need one; with no traditional identity to protect, the Gran Canaria DO is free to experiment and many of its best wines are an eclectic mix of grape varieties and winemaking techniques.

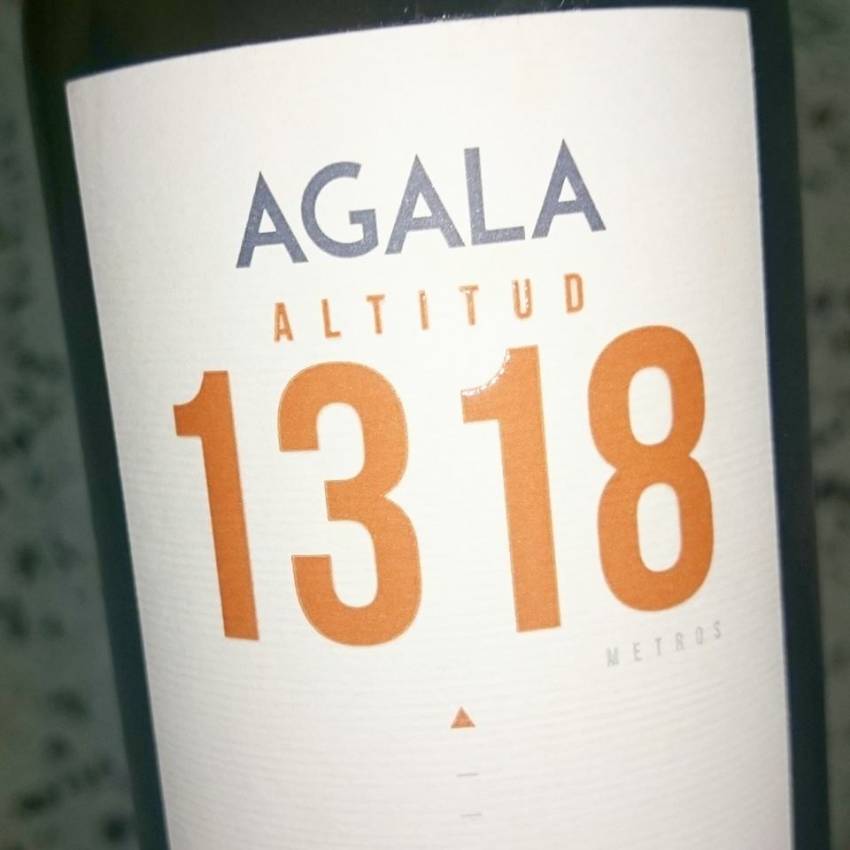

That said, Gran Canaria’s best wines do seem to share a couple of characteristics; The are either made from grapes grown in altitude vineyards (Agala, Las Tirajanas), or they are varietals or coupages of the minor varieties.

This isn’t meant to take anything away from Gran Canaria’s Listán Negro wines. Some are also excellent.

Gran Canaria’s vineyards currently cover around 300 hectares but are expanding fast.

Gran Canaria wine regions

The traditional Gran Canaria wine region is the Monte Lentiscal zone around the Bandama caldera just south of Las Palmas city. It's a fertile area with volcanic soils and a layer of volcanic picón gravel that retains moisture.

Monte was the island's original DO zone, but was absorbed by the main Gran Canaria DO. The Monte area has centennial wineries and produces some great whites and reds.

Grapes also grow well in the north, at Galdar and in the Agaete Valley; in the east around Telde and Agüimes; and all over the northern and southern highlands in areas such as San Mateo and San Bartolome de Tirajana.

Gran Canaria grape varieties

Most Gran Canaria whites are made with Listán Blanco grapes, often blended with small amounts of other local varieties such as Marmajuelo and Malvasía for extra fruit flavour.

The reds are almost all made from the Listán Negro grape,although look out for others that contain a good percentage of more exciting Tintilla, Babosa Negra, Vijariego Negro and Castellana.

Sweet Moscatel wines are common in local bars but you really do have to like your wine sickly sweet to enjoy them. Few, if any, are made the traditional way.

Gran Canaria wines to look out for

Gran Canaria whites can be spectacular. For example, the Agala 1318, named after the altitude of the vineyard, is pretty much sex in a bottle. The Caldera white (DO Islas Canarias) from the Monte area around the Bandama caldera and the Las Tirajanas varietals are all great examples. These all cost more than 10 euros per bottle and are worth every cent. Most Monte whites in the 8-12 euros bracket are fruity treats.

Amongst the reds, the widely available Frontón de Oro tinto from the San Mateo area is a mouthful of fruit and tannin and goes well with a curry, while the Las Tirajanas tinto is a light and eminently drinkable ’evening on the balcony’ red.

Frontón’s slightly sweet white is the White Zinfadel of Gran Canaria; light and eminently quaffable, it’s the Canarian wine that your gran would love.

Both sell for around seven euros a bottle. Caldera and Agala also do excellent reds with the prices up above 10 euros.

For a middle range treat, try the Mondalón, La Vica and Plaza Perdida tintos from Monte at 8 euros, or spend 18 euros on the island’s best (best marketed) red; La Higuera Mayor from the Telde area. This winery is leading the way with experiments using non-traditional grape varieties.

Where to buy wine in Gran Canaria

Most local supermarkets sell at least a couple of Lanzarote whites (El Grifo, Vega de Yuco) and Tenerife reds (Viña Norte) but you have to visit large local supermarkets such as Hiperdino, Eroski, Alcampo, Carrefour and Hipercor to find Gran Canaria wines. Mercadona doesn't bother selling any decent wine at all, Canarian or otherwise.

The El Corte Inglés department store in Las Palmas has a huge and well-curated selection in its supermarket and Club Gourmet while its independent Hipercor and Supercor supermarkets also sell a selection of quality Canarian wines. Anything you buy here will be quality but the Gran Canaria selection on offer is shamefully small.

Most big shopping centres outside the resorts have at least one gourmet shop selling ham, chorizo and wine. They all have at least a couple of good Canarian bottles. Quality souvenir shops also stock Canarian wines but do check the dates on their whites; Anything older than three years is best left on the shelf (unless it’s an Albillo or gual).

Buying wine at Gran Canaria airport is the last resort. The local produce shop in the departure has a lot of wine, but is overpriced (50% above supermarket prices) and the whites are often out-of-date.

Local markets and food fairs are an excellent place to buy wine.

The wine stall at Santa Brigida in the hills behind Las Palmas sells wines from GC, Tenerife, Lanzarote and La Palma and the owners taste everything they put on display. It’s a good place to buy the classics and to find decent Gran Canaria wines from the local Monte wine area. Prices are a couple of euros above supermarket prices, but the curated selection is worth the price.

Also in Santa Brigida, the Casa del Vino restaurant is the only one on the island that only serves Gran Canaria wine. The attached Casa del Vino museum does tastings and sell local wines by the bottle.

San Mateo market a bit further up the hill also has a wine stall (by the main door) with a small but quality selection of local and Canarian wines.

Wineries

Another option is to go directly to the wineries. Most will welcome try-and-buy visitors on weekdays, but there are some grumpy exceptions (finding out which ones is all part of the fun).

These three wineries are open during the day to drop in visitors.

Las Tirajanas winery in the hills behind Playa del Inglés and Maspalomas does a great wine and local food tasting and winery tour. Its varietals are a great way to get to know the local grape varieties.

Los Berrazales winery just above San Pedro village in the Agaete Valley does morning tours (it's where all the cruise ship passengers go) and it's Berrazales brand dry white and tinto are decent.

Hoyos de Bandama: Right by the entrance to the Bandama Caldera walks in the Monte region, this winery has an elegant tasting room and opens every day except fiestas. Its wines, made mostly from Gran Canaria grapes but also with juice imported from Tenerife, are excellent. The dry white is superb and a bargain at 2 euros a glass and ten per bottle.

The frankly quite ridiculous Lanzarote wine industry

Lanzarote is a hot, dry and largely flat island and a good chunk of it is covered in black volcanic gravel several metres thick. It gets almost no rain and is just 120 kilometres from Africa. It’s such a harsh environment that it’s one of the few places on Earth that doesn’t have native earthworms.

In short, an absurd place to try and make wine.

However, Lanzarote’s Malvasía volcánica wine is superb and this is largely due to that layer of gravel, known as lapilli or locally as picón. It acts as a sponge and absorbs moisture from the cool night air that blows over the island from the Atlantic Ocean.

Lanzarote currently has 2000 hectares of vineyards divided into 7500 plots and produces around two million bottles of wine per year.

Lanzarote wine regions

The picón that frothed out of the Timanfaya volcanoes in the 18th Century covers a large area of central Lanzarote and this is now its main wine region. The intrepid Conejeros (the Canarian nickname for Lanzaroteans) planted vines here almost as soon as the rock had cooled down.

Most of the action is concentrated in and around the La Geria protected landscape and Masdache, but there are also vineyards in the far north at Ye-Lajares. These are low yielding and unpredictable even by Lanzarote standards.

The Lanzarote growing technique

Traditionally, each vine grows in a pit in the picon deep enough for its roots to find the soil. The picon keeps the soil damp and a wall of lava chunks around the edge gives extra protection from wind. The vintner's main jobs between harvests are to keep the pit tidy, prune the vines and chuck in the odd dollop of camel pooh.

The black picon also heats up during the day and cools quickly at night, exposing the grapes to large variations in temperature. This mimics the effect of growing grapes at altitude; often the key to making good white wine on the other Canary Islands.

Even with tender loving care and plenty of camel pooh, each vine produces a tiny amount of grapes, but there are plenty of them as the land is no good for anything else.

With Lanzarote wine now in demand, both in the Canary Islands, Europe and even the States, the more productive zanja system is becoming more popular. This uses long, low walls at right angles to the prevailing wind to shelter the vines.

Another trick is to transport excess picón to new areas to take advantage of its moisture-attracting magic.

Lanzarote’s grapes are harvested by hand and some still go from vineyard to winery by camel. Once they get inside however, things in Lanzarote’s top wineries get hi-tech. Temperature controlled storage, maceration and fermentation are standard and big Lanzarote wineries now store huge amounts of grape juice at just above freezing point as insurance against lean years.

Where to try and buy wine in Lanzarote

Lanzarote has a wine culture unique in the Canary Islands. Its supermarkets and local shops sell a wide range of bottles, and its restaurants all offer local wines. Bodega visits are part of the tourist experience and you can even go on winery tours to try and buy local wines.

Here’s what local expert Julie, from the excellent Lanzarote Information website, has to say about trying and buying Lanzarote wine.

“When we first moved to live in Lanzarote we were red wine drinkers and embraced our Lanzarote wine growers, favouring the tinto produced by Bodegas Bermejo when dining out at local restaurants.

We thought we were being sophisticated wine drinkers until, during an important business lunch with Spanish colleagues, they asked us which wine we would like with our meal. Fortunately we had only requested “Bermejo por favour”. Our waiter said, “el blanco por supuesto, que nadie bebe el tinto!”: This translates as, “the white of course, nobody drinks the red!”

From that point on we started enjoying Lanzarote’s award winning white wines, developing a taste for our dry whites and enjoying an occasional glass of sweet wine at the end of a meal, instead of a dessert.

In recent years Lanzarote’s wine growers have been working hard to find a way to start producing a good red wine and we’re starting to get there, the tinto Ariana from Bodegas el Grifo and La Grieta tinto have both won awards this year.

Lanzarote is the leading wine producer from within the Canary Islands, harvesting 3.6 million kilos of grapes during August & September 2015. For many of our bodegas, wine is a family run business, with two or three generations still involved in the back breaking work of maintaining the vines and harvesting the grapes by hand each year.

La Geria wine region is a unique landscape in the world. This moonscape was created after the continuous volcanic eruptions from 1730 to 1736 when the fertile farming land was buried under a deep layer of volcanic ash. Labourers dug down through these tiny particles of volcanic stone for up to 3 metres to find the soil below and planted a vine, creating a circular hole known as an hoyo.

A few kilometres away you’ll find Bodegas el Grifo, established in 1775 and the oldest winery in the Canary Islands (and one of the ten oldest in Spain).

Here, the ash is shallower so the vines have been planted in rows allowing for a higher yield, although the harvest is still completed by hand.

Most of the D.O.Lanzarote bodegas are situated in the heart of the island, with one exception which is La Grieta in the north.

Local tips

The cheapest place to purchase wine is direct from the bodegas, but if you only have time for one stop there’s a good range of local wines for sale in the gift shop at the Monumento al Campesino in San Bartolomé.

La Grieta Malvasía Seco: Visit Restaurante El Charcón on the harbour in Arrieta to taste this dry white wine and buy a bottle to take away for 7 euros. Ricardo the owner of the bodega and restaurant is a lovely host and not afraid to experiment with his wines. He’s harvested grapes in the moonlight and sunk bottles on the seabed to mature.”

Lanzarote wines to look out for

El Grifo is the island’s oldest winery and does a great budget white. Bodegas Vega de Yuco produce an excellent dry white of the same name and a semi called Princesa de Isco. All are around seven euros a bottle and excellent value.

Both bodegas also do slightly more expensive bottles (El Grifo Colección and the blue-bottled Yaiza).

Most mid-priced Malvasía wines in Lanzarote (10 euros and up) are good quality and have the fruity zing that you expect.

However, there is more to Lanzarote than Malvasías. Look out for wines made from the Diego grape, and also for authentic sweet wines made by the traditional method (rather than by adding sugar to mediocre wine).

The vintage Tenerife wine industry

Tenerife was the historical star of the Canarian wine industry and was almost certainly the source of Shakespeare’s sack (La Palma historians will disagree about this).

It’s the only island with different designation of origin areas and it’s vast geography means that it produces the most varied wines in the Canaries.

Here’s a quick guide to Tenerife’s five official wine regions

Abona

Abona in south Tenerife gets more sunshine and less rain than the rest of the island and is hugely variable. its wineries are spread from 200 metres above sea level up to over 1600 metres (the highest in Europe).

This variation allows the DO’s wineries to blend grapes from different altitudes to create balanced wines.

Abona specialises in Listán Blanco grapes with some Listán Negro. It’s whites are famous for their blossom and tropical fruit flavours.

Valle de la Orotava

While the Orotava Valley only became an official wine area in 1995, it’s been famous for wine for centuries and its mild climate and fertile soils produce high yields. Its vines are still grown in traditional cordones trenzados; long plaits of stems that are held just off the ground in a fishbone pattern.

Located on the lowest slopes of Teide volcano, it gets plenty of sunshine and lots of moisture from the trade winds. The climate here is milder than most other areas and technically better suited to making red wine.

Even if you’ve never drunk a bottle of Valle de la Orotava wine, you’ve had it in other local wines; A large percentage of wines from this area are bottled elsewhere in the Canary Islands (using the DO Islas Canarias label).

La Orotava whites, grown mostly in the west of the zone, are known for their pleasant bitterness and fruity aromas.

The reds grown in the centre and east are smooth and light by Canary Islands standards, as you’d expect from a wine area with a mild climate.

La Orotava also produces sweet moscatel wines and even a couple of espumoso wines made from Vijariego grapes.

Tacoronte Acentejo

This north Tenerife region specialises in vibrant, fruity reds made from a blend of Listán Negro and Negramoll grapes: red wine accounts for 80% of production.

The climate is mild and wet by Canarian standards, and the soils volcanic and full of minerals.

Its vineyards, all 2,500 hectares of them, go from 50 to 1000 metres above sea level. Tacoronte Acentejo has almost 2000 grape growers and 50 bodegas and its vineyards make up 20% of the total area of vines in the Canary Islands.

It does produce some decent whites and a couple of famous sweet wines, but the reds and maceración carbonica reds dominate.

Valle de Güimar

White wines make up 80% of production at this east Tenerife region where grapes are grown on 720 hectares from sea level up to 1500 metres above sea level. Most of the vines are Listán Blanco, but Marmajuelo and Malvasía also pop up.

The best wines from Güimar come from wineries at medium altitudes, although the DO is experimenting with espumoso wines made from Listán Blanco grapes grown at lower altitudes.

Valle de Güimar wines have herby aromas and fruity flavours and work particularly well when slightly sweet (blue bottles, often with afrutado written on the label).

Ycoden Daute Isora

If there’s a better wine region name anywhere in the world, we haven’t found it yet. Fortunately, the wines, and especially the afrutado whites, live up to the name.

Located in the far west of Tenerife, this area gets hot summers, cool winters (with frost), high rainfall and humid winds during the hottest months. It’s 315 hectares of vineyards are mainly white Listán Blanco with some Malvasía, Gual and verdello.

The area is actively trying out more local grape varieties to reduce its dependence on Listán Blanco which currently accounts for 70% of the vines.

It also produces a small amount of quality sweet Malvasía wine and is experimenting with crianza reds that spend years in oak

YDI white wines are elegant with floral and aniseed notes while the rosés have pineapple and strawberry.

Tenerife wines to look out for

Where to start!

Amongst the whites, the dry Tajinaste from Bodegas Tajinaste in La Orotava is excellent, blossomy value; As is the range of Flor de Chasna whites from the Cumbres de Abona winery.

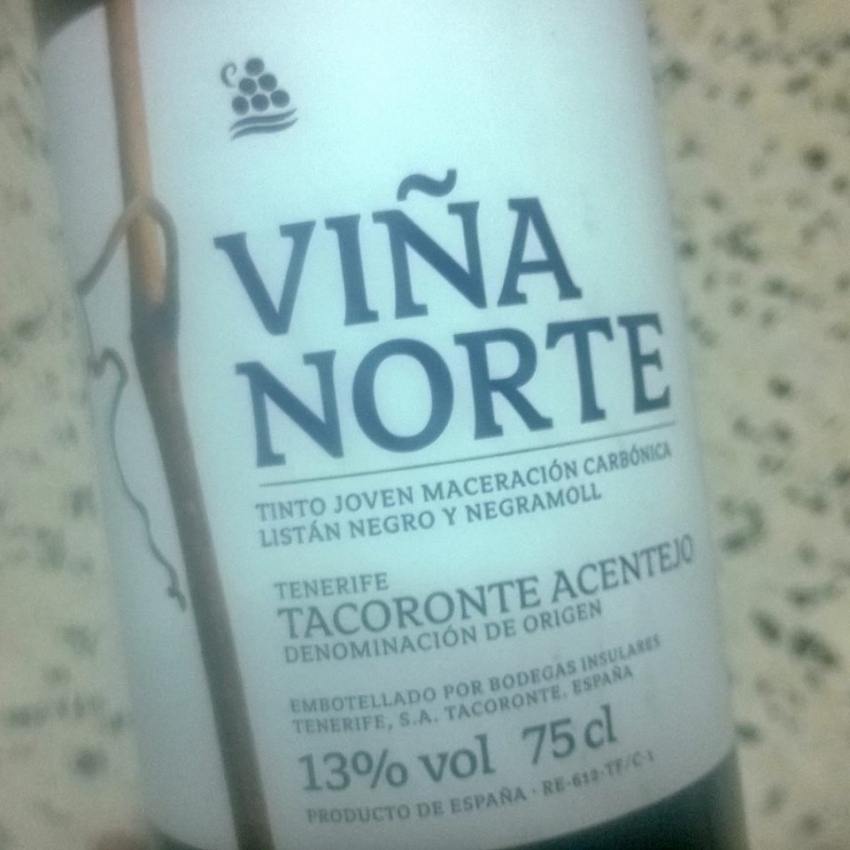

Amongst the reds, the Viña Norte maceración carbónica from Bodegas Insulares in Tacoronte Acentejo is a must try; It’s like Beaujolais Nouveau’s muscular cousin and has won blind tastings in Spain.

Balcón Canario is an excellent example of a typical Tenerife Listán Negro / Negramoll coupage, while the Viñatigo varietals are an excellent way to get to know the characteristics of the island’s grape varieties. Make sure you try a Tenerife Malvasia (Testamento is a good one) as they give Lanzarote’s famous names a run for their money.

Tenerife produces a vast number of quality vines and is the island where exploration is most likely to turn up something spectacular. We recommend travelling to the island with a teetotal friend, hiring a car, and hitting the wine regions.

Guachinches

Tenerife’s local guachinche restaurants are more than a place to try wine; They are a pillar of local life and a superb way to get to know the rural parts of the island.

Here’s how Tenerife expect Jack Montgomery from The Real Tenerife and BuzzTrips describes the guachinche.

“Guachinche – what a delicious sounding word, pronounced as far as I can ascertain as gwah-cheen-chay with the G so soft it’s like a whisper on the wind that you aren’t quite sure you actually heard.

We’d seen references to these all over the place when we first moved to Tenerife, but for a couple of years weren’t exactly sure of what they were and thought they were basically just roadside restaurants serving traditional Canarian cooking.

Wrong, wrong and wrong again; Guachinches are rough ‘n’ ready makeshift restaurants that are often set up in someone’s garage, but they can pretty much turn up anywhere – in the middle of banana plantations, in someone’s courtyard, in gardens.

Our first visit to a guachinche put us straight as to what one actually looked like. A friend led us through a maze of huertas (vegetable allotments) in Tacoronte to a shed where chunky wooden tables were laid out like an ordinary restaurant. But this was no ordinary restaurant; this was back of beyond and then some. There wasn’t even a sign identifying it as a guachinche – you had to know it existed to find it. But it was packed out with people.

Over the course of the afternoon we were brought a selection of wonderful home-cooking that ranged from ceviche (marinated uncooked fish) to papa rellena (crispy deep fried potato filled with mince) without being asked what we wanted. I think the bill came to about €10 a head including beer, wine and water.

That first guachinche was a Peruvian one and was frequented by mainly residents with some connection to Peru. Since then every other one I’ve been to has been Canarian and has generally featured pinchos (seasoned pork on skewers), rancho canario, escaldons and boiled eggs…there are always boiled eggs. They all sell wine from their own vineyard.

The origins of guachinches might not be what you think. I’d always believed the word to have Guanche origins, but apparently not. It’s a bastardisation of English and dates from a time when English merchants used to buy wine and produce direct from country folk (magos) in the hills above the north coast. As the magos prepared the order, the English merchants would say ‘I’m watching you’. Whether that was out of interest or to make sure they weren’t being short-changed is unclear but over time ‘wat-ching-you’ became ‘ gwah-cheen-chay’.

They’re quite unique to Tenerife, although Gran Canaria has a variation of them called the bochinche. The other weekend whilst walking through the plantations with a friend from La Gomera we passed one which was about as uninviting looking a guachinche as I’ve seen – behind a high wall topped with barbed wire - although the laughter and lively buzz from behind the wall showed it was a popular one. Our friend had never seen one on La Gomera.

At fiestas and wine harvest, guachinches spring up all over the place. During the rest of the year they can be found in numbers on Tenerife’s northern slopes. There are some around Güímar, Arico, and Arafo but the further south you go, their numbers diminish as they are linked to a tradition that was specific to the north of Tenerife. The best place to find them is between Tacoronte and Los Realejos.

Some you’ll never find unless you’re told about them, other can be found by following signs scrawled on cardboard nailed to trees. Restaurants that call themselves ‘guachinches’ are playing free and easy with the term and are generally aimed more at ‘visitors’ than residents. Real bona fide guachinches offer a completely different dining experience – one that is raw and about as authentic Tenerife as you can get. This is Tenerife dining for real travellers.

Once unregulated, guachinches are now bound by certain laws. They should only open for three consecutive months, offer a maximum of three dishes (none of which should be dessert or fruit) and serve only their own wine – they aren’t even allowed to serve beer, coffee or tea but they can sell water.

I’ve yet to be in one that stuck exactly to this but that’s part of what makes eating in one fun, they have a certain illicit atmosphere, like drinking at an illegal still in the forest. Just writing about them has made me yearn for a guachinche hit. Luckily we’ve got two within walking distance…buen provecho.”

The Unappreciated La Palma Wine Industry

La Palma’s wines are the best value in the Canary Islands because they are as good as all the others but don’t have the brand of Lanzarote’s Malvasías, or the big domestic markets of Tenerife and Gran Canaria.

The north of La Palma specialises in Albillo wines with rich, dry whites with peach and blossom flavours and an aftertaste of fennel.

In the drier and sunnier south of the island Malvasía thrives in the open volcanic soils and the wines are crisp and fruity.

The Canarian variety Listán Blanco grows all over the island and is used in blends and to make varietal wines.

La Palma reds are mineral rich due to the islands lava soils.

The island also produces sweet reds using traditional methods.

Here’s La Palma blogger and top astronomy guide Sheila Crosby one them.

“Sweet Malvasía is a white dessert wine from the south of La Palma. It’s too sweet to drink with fish (or to drink like a fish). In fact it’s similar to Maderia or a sweet sherry – more something you’d have at the very end of a meal with the local sweet almond biscuits.

In Shakespeare's day, Malvasía wine was known as malmsey, and it was very popular indeed. In the play Richard III, the Duke of Clarence is drowned in a butt of malmsey, which seems like a dreadful waste of good wine to me.

Malvasía comes from Fuencaliente in the south of the island, and most of the vines are trained very low to the ground to prevent the grapes from drying out, which must make for back-breaking work.

Bodegas Teneguia does an award-winning sweet Malvasía which is aged for 16 years. It’s called “Calidad Estelar” – Star Quality, in honour of La Palma’s amazing dark skies. It seems to be winning prizes all over the place.

It won “Best Canarian Wine” at Agrocanarias2012, and a gold medal at the international Wine Festival Vinalies Internationales 2012 in Paris.

Obviously I’m not the only one who thinks it’s heaven in a glass.

Also try the Casa Museo de Vino Las Manchas at Las Manchas de Abajo (Los Llanos de Aridane). It has a great selection of vintage wine-making equipment and does tastings.”

La Palma wines to look out for

Any Albillo varietal from La Palma is worth trying. The Vega Norte is excellent at around 8 euros as are the dearer Mattias i Torres and Nispero. Vega Norte also does a tea wine.

In south La Palma, the Bodegas Teneguía cooperative does a great dry white Malvasía.

Where to find La Palma wines

Most supermarkets in La Palma stock a selection of local wines, and bodegas sell direct. Ask in local restaurants and don’t be afraid to try wines that you don’t recognise; La Palma wines, and especially the whites, are great value.

Grapes in one basket: La Gomera

La Gomera’s wine has improved no end since the 1980s, when temporarily blindness was a common consequence of opening a second bottle. But it still hasn’t made much inroad into the wider Canarian market and is almost impossible to find anywhere off the island.

This is a shame since the forastera blanca grape shows great promise and the island is well suited to grape growing.

The only wine that makes it off the island is the Altos de Garajonay dry white made by the island’s official wine cooperative. A passable dry, fruity white that retails for five to six euros a bottle, it hints at Forastera’s potential.

The grape is a potential marketing superstar if the island’s 14 wineries can coax great wines out of it.

Where to buy wine in La Gomera

There’s a wine information point in the municipal market in San Sebastian, and a wine shop at Arure in Valle Gran Rey. Also look in supermarkets, stop at the faintest sniff of a winery, and ask in local shops and supermarkets.

Some La Gomera wines also make it over the sea to South Tenerife shops and supermarkets.

If you find something good, let the world know.

El Hierro

The grape growing industry on El Hierro is best described as fragmented. The island’s 200 vineyards are small, family-owned affairs and cultivate a total of 250 hectares of mixed vines. Most are at El Golfo on the west coast where they grow amongst the pineapple plantations.

El Hierro’s most famous and widely available wine is its La Frontera white made by the island’s main cooperative.

The dry white (tall green bottle) at seven euros a bottle is excellent value. A mix of acidic Verijadiego grapes and fruity Listán Blanco, it’s a light, fresh wine that is great with seafood.

The semi sec from Viña Frontera (blue bottle, about six euros in supermarkets) is excellent with great fruity flavour and a definite taste of pineapple. If you like semi wines, this is one you have to try. Frontera’s young red is a lively tinto that needs to be opened a couple of hours before drinking.

Where to buy wine in El Hierro wine

To try El Hierro wines other than Viña Frontera, you have to go to the island, or search supermarket shelves and gourmet shops in Tenerife.

Canary Wine notes

Ben Jonson: Inviting a friend to supper

But that which most doth take my Muse and me,

Is a pure cup of rich Canary wine

Traditional wine presses

The days of wooden lagar wine presses are over, but you still find old ones them in the Canarian countryside. They consist of a screw press set in an open-sided barrel with a huge wooden lever used to crush the grapes.

Canarian lagares are unique in Spain where most grapes were traditionally squashed by feet. It’s likely that the lagar descends from the heavy-duty sugar cane presses common in the Canaries before vineyards replaced cane plantations.

Young Whites

Most quality Canary Islands wines are made in stainless steel tanks with temperature controlled fermentation.

It means that they are fresh and fruity and made to be drunk quickly; Many Canarian white wines lose their flavour after 18 months in the bottle, especially if they are left knocking about in warm storerooms or on supermarket shelves.

We advise you to check the labels of Canary Islands white wines and avoid any that are more than two years old. You may be fine with older bottles, but lots are past their best.

It’s always a shame to splash out on a great bottle of wine and not taste it at its best.

The Listán Negro dilemma

Canarian wineries have fretted about the inadequacy of Listán Negro (and Negramoll) for years. While it does produce some great wines, it isn’t a superstar grape anywhere else. In the US, Mission grapes are a historical anecdote and only a few wineries bother to press them.

While good Listán Negro varietals are fruity and spicy, most Canarian wineries focus, with some success, on blending it with less widespread varieties like Tintilla and Vijariego Negro.

However, the doubts about whether Listán Negro linger on. Expect to see big Canarian wineries experimenting more with blends of other grapes and even, but don’t say this out loud, non-autochthonous grape varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Tempranillo.

Maceración carbónica wines

When Canarian winemakers brought in modern winemaking equipment, they couldn’t work out why their young red wines didn’t taste as good as their dad’s.

It was because the grapes used to be stored in cool cellars for a few days until the farmer had enough to press. During this rest period, the grapes started to ferment in their skins and used up all the oxygen in the cellar. They absorbed fruity flavours from the skins without any harmful oxidation.

The result was fruity young wines that tasted great but didn’t last. When wineries modernised, they stopped leaving the grapes lying around and the flavour suffered.

Winemakers now duplicate the cellar effect by putting their red wine grapes into cool, steel tanks and pumping them full of CO2 gas. This lets the grapes ferment away and gives the wine a real berry flavour.

To try wine made this way, the same method the French use to make Beaujolais Nouveau, look out for bottles that say ‘maceración carbónica’ on the label.

Don’t buy if they are more than two years old as this wine loses its flavour fast. Also, chill your bottle as MC wines taste best at around 13ºC.

Oaking the whites?

Some Canarian winemakers insist on taking superb white wines and tempering all that fruity freshness by leaving them in oak barrels. The effect can be positive but is often overdone.

By all means try an oaked Canarian white, especially if you like oaked Chardonnays, but the best Canarian whites are dry, fruity and go straight from the fermentation tank into the bottle.

You don’t always get the choice as some wineries don’t mention oaking on their labels. Grrrr!

Exploding banana wine

A few years ago an eccentric German winemaker decided that what the world needed most was champagne made from bananas. Nobody took him seriously because everyone in the Canary Islands know that the best thing to do with a banana is eat it.

Undeterred, he moved to Gran Canaria, made his wine, put it in his cellar and waited for the magic to mature.

Unfortunately, a calima wind came in and the extra warmth made all his champagne bottles pop their corks. 10,000 bottles of banana champagne ended up on the cellar floor.

It was a messy and ignoble end to the great Gran Canaria banana wine experiment.

Until Platé!

Platé is a slightly sweet white wine made with bananas. It tastes, unsurprisingly, of bananas but is subtle and nothing like those lurid bottles of banana liqueur that have sitting on souvenir shop shelves since the 1970s.

Platé is a good attempt and worth trying if you like sweet wines and bananas. Otherwise, it’s still more at home on the souvenir shop shelf than amongst the real wine.

Trying the best Canarian wines

We try dozens of Canary Islands wines every year and review them in this Canary Islands wine Facebook group. Please feel free to join and add your own reviews.

The best wines we try make it into the wine section of the Gran Canaria Info website where we also publish regular articles about Canarian wine.

Tried & Tasted: Guide To Canary Islands Wine

The wines of the Canary Islands, born of lava and sunshine and pressed from rare and ancient grapes, are a the highlights of the islands that most visitors miss out on. We want to change that, so here's the book that helps you understand and enjoy them.

Gran Canaria Wine: Great Las Tirajanas Red

8 Fascinating Facts About Canary Islands Wine

The history of Canarian wine goes all the way back to the Ancient Greeks, and vines from the Canary Islands were the first to be planted in the Americas and Lord Nelson learned to drink with his other hand using wine from Tenerife.

La Palma Wine: Vega Norte Blanco Is Light And Tasty

The budget dry white from one of La Palma's top wineries, this is a fruity and drinkable wine perfect for a hot day.

The Best Canary Islands Wines To Drink With Curry

Canary Islands wines have the intensity and fruit to stand up to a good curry so if you feel like a takeaway, then look out for these bottles in the shops.

Hooray: The Canary Islands Grape Harvest Starts Any Day

The wine grape harvest, the earliest in the Northern Hemisphere, is due to start any day. Vineyards expect a bumper harvest.

Ever Tried Canary Islands Banana Wine?

When we found Platé banana wine, we just had to try it. What could be more Canarian than wine made from bananas?

Santa Brigida Market: Fresh Veggies And Great Wine

Santa Brigida weekend market is where Las Palmas' well-to-do go to be seen buying their fruit and vegetables. The fruit and veg are good, but prices are higher than at San Lorenzo or San Mateo. There's even an organic food stall.

Lanzarote White Wine Taste Off

With Lanzarote's La Geria, Vega de Yuco and El Grifo white wines common on Gran Canaria supermarket shelves and selling for seven to eight euros, we tasted all three so that you know which is the best buy.

Viña Norte: Award Winning Carbonic Maceration Red From Tenerife

Tajinaste Blanco: A Fantastic Tenerife White Wine

The Costa Meloneras hotel in Gran Canaria have this on their a la carte restaurant wine list and it's a great example of a dry Canary Islands white.

Western Wonder: Teneguia White Wine From La Palma

This excellent La Palma dry white is superb value and rivals any Spanish white you can buy for the price in Gran Canaria's supermarkets.

Canary Islands Wines: La Palma's La Gota

This is one of the best value Canarian white wines and is easy to find in Gran Canaria's supermarkets.

Gran Canaria Wines: Robust Frontón de Oro Made the New York Times

"Not without tannins" said the New York Times review of this Gran Canaria red made with local listan negro grapes. It was right: Fronton has a hint of wood resin from the oak barrels but also enough fruit and herby notes to make it a great value Gran Canaria red.

Canary Islands Wines: Lanzarote's Fizzy Lava Juice

Lanzarote's volcanic soils produce many of the Canary Islands' best white wines and their only bottle of fizz. Fortunately the El Grifo Brut Malvasia is a cracker.

Gran Canaria Wines: Agala 1318 Altitud (was) Sex in a Bottle

The Winery

The Agala winery is called Bodegas Bentayga. It's between Tejeda and Artenara and at up to 1318 metres above sea level it's one of the highest in Spain. The vines grow on small terraces on steep terrain and experience a vast range of temperatures. This area of Gran Canaria gets snow during cold winters and can reach over 40ºC during hot summers.

As with most Canarian wineries, Bentayga grows local grape varieties and hand picks the grapes: 1318 is made with a blend of Albillo and Vijariego.

Visits are possible but only from Monday to Friday, minimum six people and 72 hours notice. They cost 8 euros per person and include the chance to buy wine at bodega prices. Book here.

Agala 1318 is available in good wine shops and at the wine stall in the Santa Brigida weekend market.

2021 reviewed of oaked Agala Altitud dry white wine

This wine has been one of the best Gran Canaria whites for several years. Grown in South Central Gran Canaria, it had that zing you get from blasting white wine grapes with the extremes of temperature and climate (snow to 40C) you get at over 1000 metres above sea level.

Back in 2015 we reviewed it as "a floral nose with apricot and a touch of sweetness. In the mouth, it is dry but rich with well-balanced acidity. You get intense fruit and flowers, and a floral finish with a little bitterness".

It was all about the blossom!

The concept has evolved since then and this wine now spends time sobre lías in French oak barrels.

Oak and dead yeast add intensity and depth of flavour at the expense of freshness. But is it worth all that extra effort? Can you take an excellent "drink now" Canary Islands wine and turn it into something deeper? Why would you want to?

Oak, melon and banana on the nose. Quite exciting at first sniff but there's a tired hint to the wood after a few more.

Good acidity in the mouth from the vijariego, richness from the albillo. A hint of butter and vanilla from the oak and lías. Melon and banana.

Blah blah blah!

Bring back the old version we say. The oak and butter don't make up for the lost blossom and freshness.

Check our latest Gran Canaria and Canary Islands wine reviews on our Canary Islands Wines Facebook Group.

Great Value Canary Islands Wines You Have To Try in Gran Canaria

The Canarian wine scene hasn't buzzed this much since Shakespeare's time. New wineries start up every year and there's always a new wine to try. However, because most wineries on the islands are small you can only buy them close to where they are grown. Great if you have the time and transport but a pain if you're in Gran Canaria on holiday.

Gran Canaria Info recommends:

- Default

- Title

- Date

- Random